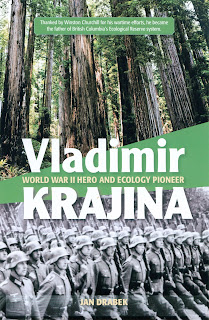

Few people live lives that would make for an interesting

book, and not all those who have lived such interesting lives are well known.

Vladimir Krajina, a Czech botanist who worked at the University of British

Columbia in the second half of the 20th century,

fits this description. Biographer Jan Drabek, himself a Czech émigré living in Vancouver, in Vladimir

Krajina: World War II Hero and Ecology Pioneer, has written an insightful and

informative biography that will be of interest to both WWII and ecology

enthusiasts alike.

Drabek’s biography is essentially two distinct parts,

reflecting the dichotomy of Krajina’s life. The first follows Krajina’s life in

Czechoslovakia as a member

of the Resistance until his escape to London

in 1948. The second part documents Krajina’s life in British

Columbia where he worked as professor and researcher at the University of British Columbia’s botany department.

What is similar in both halves of Krajina’s life is how important was the work

he was doing, and how unknown it was – and still is – to the majority of

people. For myself, I was aware of Krajina’s botanical and ecological work through my university studies, but had no idea of his experiences in WWII and knew little

of the events in Czechoslovakia

during this time.

Krajina was a student at Charles University in Prague when

Czechosolvakia was a fledgling democracy after the fall of the Austro-Hungarian

Empire and before occupation by first Nazi Germany and then as a Communist

country under the influence of the Soviet Union. Drabek hypothesizes it was

this time living in an independent democratic country that Krajina felt

strongly about, and when it was threatened by Nazi invasion he was compelled to

play a role in protecting it.

By 1939 the Nazis had closed all of the universities in Czechoslovakia,

and Krajina was no longer a botany professor but full time Resistance member.

Krajina became a leading member in a group pivotal in the encoding, sending and

receiving of intelligence-related information between Czechoslovakia and its exiled government in London. For example, it

was Krajina’s group which relayed the intelligence that the Wehrmacht was

planning to attack British-controlled Egypt

and the Suez Canal, allowing some two months’

warning for precautions to be taken.

Drabek explains that Krajina was an ideal person for this

kind of work because of “his enormous self-discipline and strict observance of

rules of conspiracy”. However, he also intimates that Krajina was like the

character in the Disney film “Ferdinand the Bull”:

“…a magnificent animal chosen for the bullfighting ring. But

Ferdinand prefers to smell the flowers instead of fighting and, eventually…is

returned to his pasture…sitting there still, under his cork tree, quietly

smelling his flowers. The flower-loving Resistance fighter may have been a

thorn in the Germans’ side, but unlike many of his companions, he refused to

carry a gun.”

At one point in the war the author’s father had given Krajina a

book of flower drawings done by Czech artist Josef Manes. When Krajina had to

flee the Gestapo, he returned the book for safekeeping; the author’s father

noticed that even during this dangerous time Krajina had made corrections in

pencil to the names for each flower.

Between 1939 and 1943 Krajina was regularly on the run from

the Gestapo, hiding in sympathizers’ homes, meeting intelligence contacts in

the streets after dark, and somehow managing to send upwards of 6000 radio

messages each year. However, by early 1943 Krajina was captured, interrogated

and sent to Terezin concentration camp until the end of the war. Post-1945 Czechoslovakia saw political struggles as various

ideologies fought for supremacy. According to Drabek, Krajina again felt compelled

to be active politically instead of returning full-time to his botany work

because it was important to him that Czechoslovakia return to the

democratic nation it was before the Nazi occupation. Instead, Krajina found

himself arrested and threatened with execution by the new Communist government

unless he agreed to cooperate. Again showing his principles and courage,

Krajina arranged to escape by skiing across the border to the US military in Germany. Once finally made his way

to England

he arranged for the escape of his wife and two children.

Reunited, the Krajina family made its way to Vancouver, British

Columbia. Working in the botany department at the University of British Columbia, Krajina made his mark with his ecological approach to forest

research and the influence this had on the province’s forestry industry. This

perspective was unique at the time, as in a report Krajina wrote for a major

forest company in 1954 he said:

“Forest

resources are natural resources which should not be exploited by the methods

used in mining, where the products cannot be regenerated. Forest

resources should be kept for a sustained yield through all generations.”

Krajina went further, saying that virgin forests were rapidly disappearing

without thorough analysis, and that a representative portion of them should be

saved intact for future study, an important consideration when areas

needed to be reforested after logging. This was the basis of Krajina’s research into what were

later termed biogeoclimatic zones, 14 of which he identified for British

Columbia and which are still referred to today. By the late 1960s the

provincial government was discussing setting up ecological

reserves under the models proposed by Krajina, passing the

Ecological Reserve Act in 1971. For the rest of his life Krajina was an

ardent campaigner for establishment of reserves to protect sensitive

ecosystems, always having to argue for conservation over immediate logging /

economic opportunities in the short term. In 1973 an ecological reserve was established on

Haida Gwaii bearing Krajina’s name, its literature describing it as “an outdoor

museum and laboratory available for botanical, wildlife and geographical

fishery”.

Drabek’s biography is enriched by the closeness of the author

to its subject. His father worked closely with Krajina during WWII in the Resistance

movement, and the author was the same age as Krajina’s daughter and even

attended the same school. Drabek has written a detailed portrayal of a man who

spent his life engaged in principled struggles for democracy and the

environment, from which and from whom much can learned and applied today.

No comments:

Post a Comment